Alexander's road back

In Coldwater, Kansas, where school hallways and gym walls carry decades of shared history, Trace Alexander is once again a familiar sight. He watches practice, spends time with teammates and settles into the routines that define life at South Central — ordinary moments that carry uncommon weight.

A year ago, moments like this were uncertain.

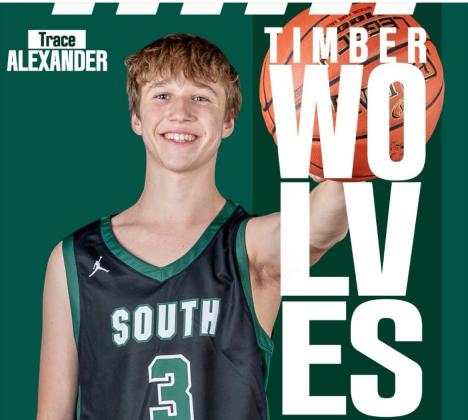

Alexander, a junior at South Central High School and the youngest of seven siblings, is back where he feels most at home — around his friends, his teams and his family.

“He’s got a lot of friends, a lot of buddies and is just kind of an ordinary kid,” his father, Wynn Alexander, said. “He gets along with people and is just a good old social kind of kid.”

Trace was born and raised in Coldwater, the home of South Central High School, which serves students from Protection, Wilmore and surrounding rural areas. Sports were constant — especially football in the fall and basketball in the winter — and so were friendships that stretched back to early childhood.

“Growing up in Coldwater is good,” Trace said. “We all hung out, all of us friends. We all did sports together. You know, we’ve been together since we were really little. We all went to preschool, elementary, middle school.”

Trace followed six older siblings who helped shape him long before he reached high school. Three sisters played college basketball. An older brother’s run to the state tournament became a reference point for Trace and his friends as they grew up watching South Central teams chase big moments together.

“They pretty much taught me everything I know,” Trace said of his siblings. “They taught me sports. They helped me a lot growing up.”

That foundation was shaken in the fall of 2024, when what appeared to be a routine football injury turned into something else. Trace hurt his knee near the end of the season. Imaging revealed an abnormality in his tibia. A biopsy followed. On Christmas Eve, the family received the diagnosis.

Bone cancer.

Treatment began at the start of January of 2025 and stretched into October. Trace underwent chemotherapy primarily in Wichita, following a demanding schedule that often kept him in the hospital for long, grueling stretches. The physical toll was significant. The emotional strain was unavoidable.

But his parents remember one thing more than anything else.

“He never complained,” Wynn Alexander said. “The only thing he ever wanted was to come home. The type of chemo he was getting had to get out of his system. He’d be in the hospital five to seven days, get two days off, then start back up. And then the other chemo was harder on him. …He just went through with it and did it.”

His mother, Kim Alexander, recalled one early moment when the weight briefly surfaced, when Trace told her he wished he had said no to chemotherapy. After that, she said, the complaints stopped.

“He just wasn’t a complainer,” she said. “He just wasn’t. That probably made it seem easier, but yet harder, because you knew he was really sick. It was so hard to watch, but it made it easier.”

Along with the Alexander family’s love and determination to stay by his side, his friends often visited, and were greeted by the same subtle comedy they’d known for years.

“He was always joking,” Kim Alexander said. “He’s really funny. Even when his friends would come visit and it looked quiet, if you stood back and listened, they were saying funny stuff.”

Hospital staff took notice of Trace’s charisma as well. Nurses requested him as a patient. Some stopped by even when they were not assigned to him. His calm presence left an impression.

“I think he had just a nice personality and mentality,” Kim Alexander said.

While Trace focused on getting through treatment, the community around him did what they could to help. Fundraisers followed. Messages of encouragement and hope arrived from strangers. Schools across the SPIAA league organized gestures of support. South Central students and staff rallied behind him and anxiously waited for updates on his condition.

“It was awesome,” Trace said. “I’d get letters and gifts from people I didn’t even know — churches from around the state sending me love. Especially this community. They helped me through a lot of stuff. They were backing me.”

The bell-ringing ceremony marking the end of chemotherapy became one of those shared moments. Friends and family filled the space. The turnout was so large that hospital staff later changed protocol, creating a designated room for future ceremonies. At South Central, the ceremony was live-streamed in the cafeteria with the entire school watching.

For the Alexanders, it was a milestone — not a finish line.

Doctors describe Trace as “chemo free,” with one remaining mass that is no longer growing. Ongoing monitoring remains part of his life. But the day carried relief, gratitude and togetherness.

At South Central, the winter basketball season unfolded alongside the early days of Trace’s treatment. The Timberwolves navigated injuries, a short bench, and the emotional strain of their friend and teammate’s diagnosis. Despite the challenges, they entered sub-state with high hopes and an 18-2 record.

Already a competitive group led by head coach Bud Valerius, the team received a major boost in motivation with news that if they advanced, Trace had a shot to travel with them to the state tournament if his numbers reached a required level.

“I know his mom said that was a big motivator for him, but it was also a big motivator for the team,” Valerius said. “So during pregame breakouts and after all the playoff games it was said that ‘we have to get Trace to the state tournament!’”

Both accomplished their goals, winning the semifinals against Meade and Kiowa County in the finals in thrilling fashion by one point apiece.

It was then the selflessness of teammate Tyler Pauly that provided the last step to ensure Trace made the trip with the team to the state tournament in Dodge City. The then-junior didn’t hesitate to volunteer to give up his seat on the bus and rode separately.

Once at state, South Central won their first round and semifinals games by double digit margins, but couldn’t overcome Olpe in the title game. An abrupt conclusion that stung at first, but the season’s meaning extended far beyond the final score.

“In the moment, the pain of the loss was real,” Valerius said. “But looking back, I couldn’t be more proud. They showed what true character, perseverance, and what brotherhood looks like.”

“They played for each other,” Valerius said. “... but most of all they played for Trace.”

Despite not getting the storybook ending, the Timberwolves got a sequel. Their perseverance carried forward into the fall as South Central’s football team completed an undefeated run and won the school’s first state championship since consolidation in 1999. Trace stood on the sideline for the playoff push, part of it in every way that mattered.

“It was exciting for him because he could be part of it,” Wynn Alexander said. “He wasn’t on the field, but he was there.”

Today, Trace has returned to school full time. He attends practices, helps when he can and remains a familiar presence among teammates. Physical limitations remain — football is no longer an option — but possibilities still exist. Golf offers a path forward. Basketball remains a conversation to be guided by doctors.

Through it all, the routine has returned. School. Practice. Friends. The same hallways, the same gym, the same small-town rhythms.

Trace Alexander is back inside them — not as a symbol, not as a headline, but as himself — surrounded by the people who never left his side.